What to do when you grow up in a place where you feel out of tune, where you don’t see a clear future for yourself? A place that doesn’t quite match your desires, or doesn’t seem to do sufficient justice to the possibilities of the human spirit? A place that isn’t friendly to your eyes and lungs, with its „dirty hoods“ and „dusty roads“, as in Springsteen’s „Thunder Road“? You might simply leave, unless… Unless there’s something that keeps you there: family, friends, work, a house, a sense of belonging. In that case, musing about an escape can be an effective coping strategy to deal with your situation. Someday, you say to yourself, you will hit that two-lane road to a far-away promised land – and if not in reality, that road and land will surely exist in your dreams.

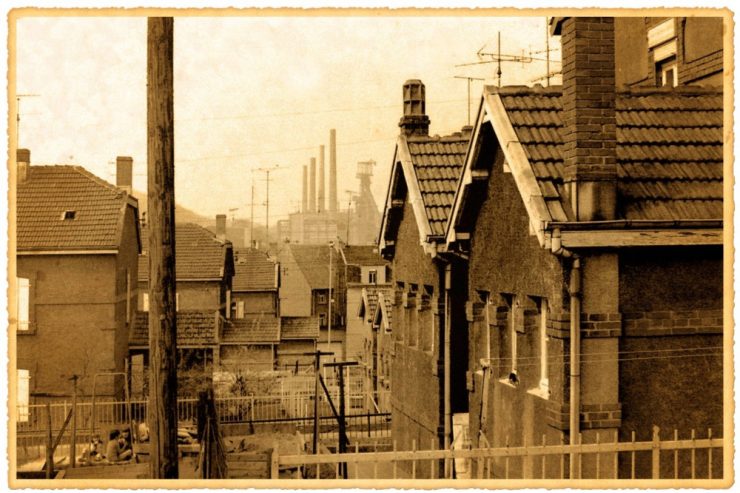

Industrial regions like the Minett are places that easily spur the ambivalent sentiments described above. Despite well-developed feelings of local identity and pride, life in the Minett indeed came with very particular drawbacks. Excessive corporate power was one of them. Steel companies were involved in virtually all aspects of life: apart from providing a livelihood to thousands of families, they had established schools, sponsored sporting clubs, and so on. This industrial „omnipresence“, as the former ARBED employee Jean Back-Hoffmann has called it in a recent article for forum, could be very stifling to those who envisaged an alternative life trajectory. Another unmistakable drawback was environmental pollution. „Im Viertel Quartier Italien [in Düdelingen], wo ich die Kindheit verbracht habe”, Back-Hoffmann notes, „war – schon allein optisch, geräusch- und geruchsmäßig – die ARBED, die allgegenwärtige ARBED!“ The omnipresence of factories did indeed imply an omnipresence of pollutants such as smoke and dust.

In her 1998 book „Für die Katz’“, Nelly Moia, herself a native of Esch, has signalled that inhabitants of the Minett were rather hard-boiled with regards to air pollution. Essentially, this was a matter of nurture, Moia suggested: „Wer seit zartester Kindheit den Himmel rotbraun verdunkelt sah …“ Yet, while it is true that inhabitants of industrial regions often had (and have) quite a high mental tolerance level vis-à-vis pollution, they definitely did not accept environmental degradations at any price. Indeed, it is not widely known that criticism of pollution was already voiced long before the advent of the present-day environmental movement and green politics. Usually, these critiques pointed to a conundrum that remains relevant up until today: how could the demands for health and quality of life be squared with the demand for economic development?

As early as April 1914, just three months before the start of the First World War, the newspaper Obermosel-Zeitung voiced concerns about the so-called „Rauchplage“ in Esch: „Nicht weniger als 30-40 Hochofenschlote in nächster Umgebung speien Tag und Nacht ihren Inhalt auf die Minettehauptstadt herunter. […] Nur ein schwacher Trost ist es für die Escher, zu hören, daß auch an anderen Orten die Rauchplage als ein großes Uebel empfunden wird […].“ In this context, the term „Rauchplage“ (as well as its variant form „Staubplage“) carried almost biblical overtones and referred to a seemingly irreversible fate that had befallen the people of the Minett. From the interwar period onward, however, complaints became less fatalistic and markedly more pungent. In a 1928 critique of local politicians in Differdange, the Escher Tageblatt for instance continued to have recourse to biblical metaphors, but not without drenching them in irony: „[…] Sie hatten dem bösen Götzen ‘HADIR’ gedient, und die Interessen ihres Volkes vernachläßigt. Als Entgelt dafür, hat dieser mit seinem Staub die Luft verpestet, die Straßen, Pflanzen und Dächer mit Staub belegt, denselben durch Türen, Fenster und Ritzen ins Haus dringen lassen, die Lungen und Augen der Säuglinge sowohl wie der Erwachsenen damit gefüllt. Hatten sie nicht dem Götzen unzählige Liebesdienste erwiesen, trotzdem sie dem Volke gelobt hatten, dem geizigen Brotherrn auf die Finger zu klopfen?“

With comments like these (and many other examples can be found for the interwar period), the Tageblatt indirectly called for increased research and investments in smoke filter systems, even though this technology was still in its infancy throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Yet, after the Second World War, it became increasingly clear that companies like ARBED and its opposite number HADIR of Differdange (absorbed by ARBED in 1967) often postponed costly investments in efficient filter systems, with the sole aim of safeguarding high profit margins. In the 1950s, even the conservative Luxemburger Wort started to publish scathing readers’ letters, targeted at the local captains of industry: „In Differdingen läßt man die Menschen kaltblütig im Staub ersticken. Was nützt es uns, wenn die Industrie uns Arbeit und Brot gibt, gleichzeitig jedoch unsere Gesundheit untergräbt und uns die Freude am Leben nimmt?“ It was a pressing, even existential, question, which went right to the heart of what it actually meant to live in a „dirty hood“. Some years later, the communist newspaper Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek (1972) joined in the debate by pointing out that the socio-economic injustices of the Minett were also, in essence, environmental injustices: „Wo ARBED-Schlote rauchen, fallen neben Maximal-Profiten und fetten Dividenden auch Staub und Dreck, und es darf doch wohl nicht so sein, dass sich die Hüttenbosse an der Riviera und in St. Moritz prächtig erholen, während zuhause die werktätige Bevölkerung kräftig Staub schlucken darf.“ For the inhabitants of the Minett, there was indeed no two-lane road that might simply lead them to a sun-baked Riviera or to the snow-capped mountains of St. Moritz. Unless, perhaps, an imaginary one.

About the author

Jens van de Maele has published on architectural history, urban history, and environmental history, is a postdoctoral researcher at the C2DH (University of Luxembourg) and is currently working on the Esch2022-project „Remixing industrial pasts in the digital age“.

Thunder Road

(…) Well now I’m no hero

That’s understood

All the redemption I can offer girl

Is beneath this dirty hood

With a chance to make it good somehow

Hey what else can we do now

Except roll down the window

And let the wind blow back your hair

Well the night’s busting open

These two lanes will take us anywhere

We got one last chance to make it real

To trade in these wings on some wheels

Climb in back, heaven’s waiting on down the tracks

Oh come take my hand

We’re riding out tonight to case the promised land

Oh Thunder Road, oh Thunder Road

Oh Thunder Road

Lying out there like a killer in the sun,

Hey I know it’s late, we can make it if we run.

Oh Thunder Road, sit tight, take hold Thunder Road

(…)

Bruce Springsteen

(from the album „Born to Run“, 1975)

Sony Music Group/Eldridge

This Hard Minett Land

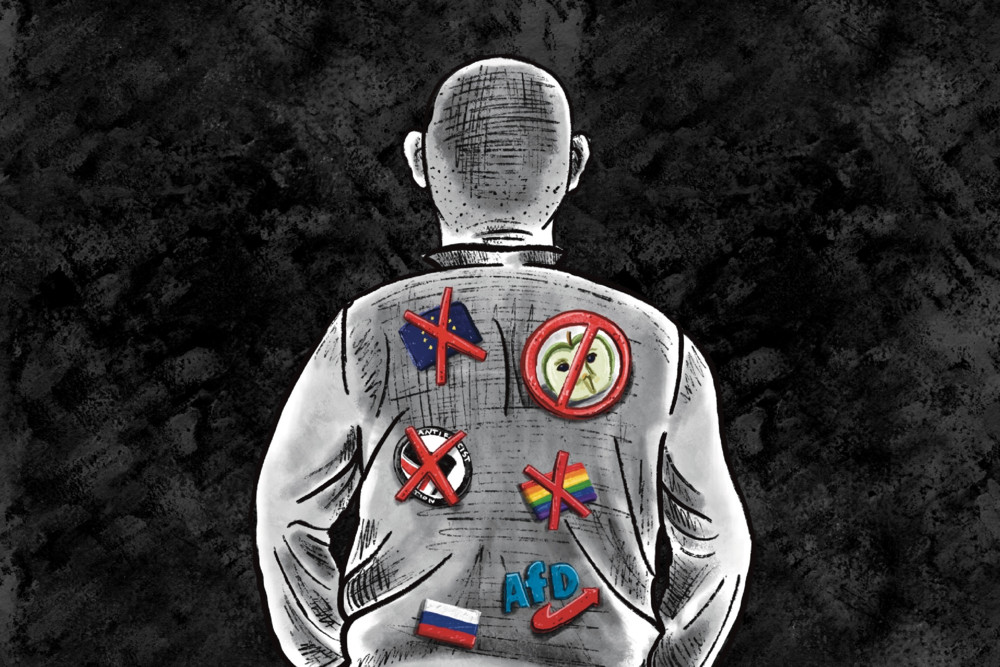

Von März bis Oktober 2022 laden das Tageblatt, das Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C²DH) und capybarabooks die LeserInnen jeden Freitag zu einer besonderen Entdeckungsreise durch Luxemburgs Süden ein. Rund vierzig SchriftstellerInnen und HistorikerInnen lassen sich von Bruce Springsteens Songs inspirieren und schreiben Texte über das luxemburgisch-lothringische Eisenerzbecken, „de Minett“, sowie über diejenigen, die dort geboren oder dorthin eingewandert sind, dort gelebt, gearbeitet, geliebt, geträumt, gehofft, gekämpft, Erfolg gehabt oder versagt haben. Begleitet werden die Texte in deutscher, englischer, französischer und luxemburgischer Sprache von Illustrationen des Luxemburger Künstlers Dan Altmann. Im Herbst erscheinen sämtliche Texte und Zeichnungen dann versammelt in Buchform bei capybarabooks. Bis dahin heißt es: „Son, take a good look around/this is

your … Minett Land!“

Zu Demaart

Zu Demaart

Sie müssen angemeldet sein um kommentieren zu können